Key Takeaways

- Reframe procrastination: It’s neurological, not a character flaw: For individuals with ADHD, procrastination is a symptom of executive dysfunction; these are genuine neurological differences impacting planning, motivation, and self-regulation, not laziness or poor habits.

- Executive dysfunction sabotages task initiation: Difficulties in getting started, staying organized, or following through are driven by impairments in executive functioning, making it harder to begin or sustain focus, not due to a lack of effort.

- Self-regulation and time blindness undermine productivity: Challenges with monitoring emotions, impulses, and most notably the perception of time (“time blindness”) result in persistent delays, missed deadlines, and overwhelm unique to ADHD.

- Motivation is biochemical: Dopamine drives action: The ADHD brain experiences dopamine and reward signals differently, which makes “just get started” implausible without strategies or supports that directly target motivation.

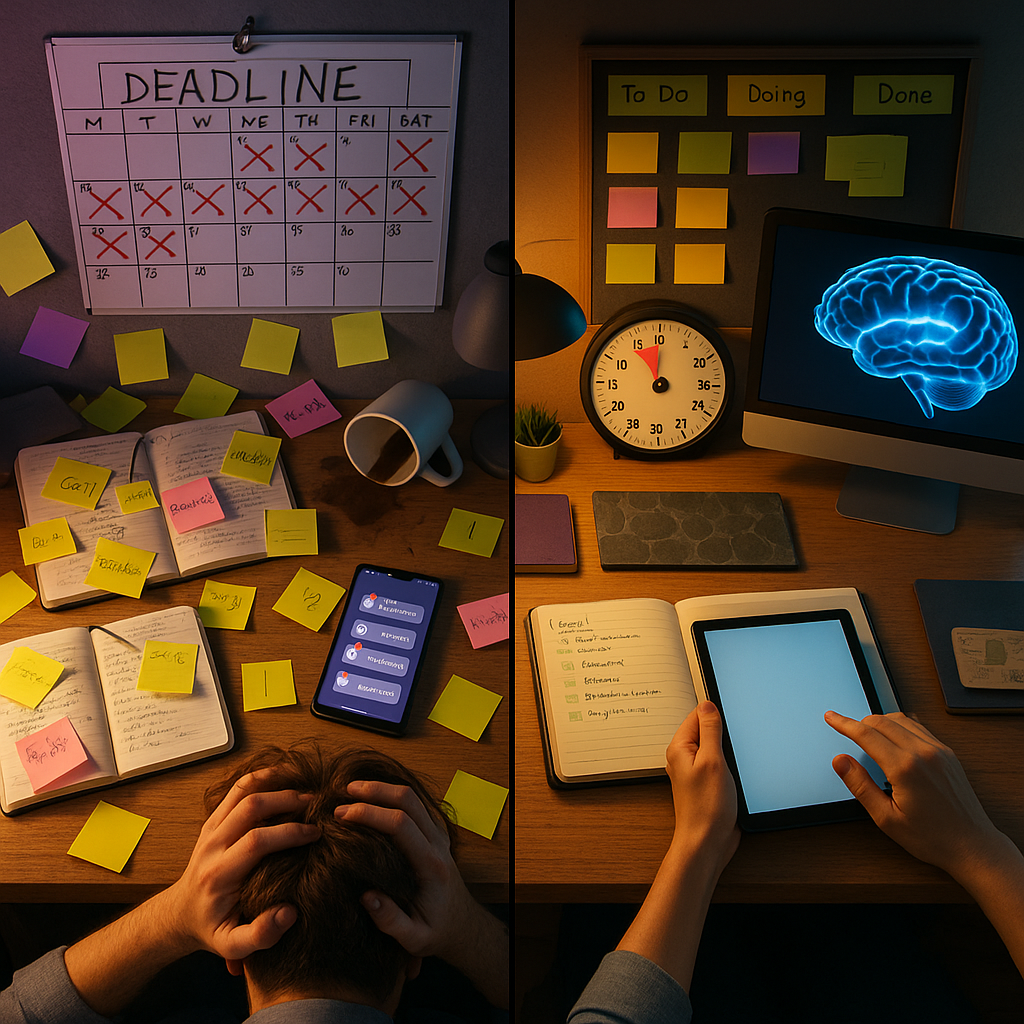

- Traditional productivity hacks fall flat for ADHD: Mainstream advice designed for neurotypical brains often ignores executive dysfunction, leaving people with ADHD feeling frustrated and stuck when standard planners and reminders fail.

- Systems, not willpower: Build ADHD-friendly workflows: Meaningful progress relies on external systems (clear steps, visual reminders, body doubling), rather than sheer self-control or willpower.

- Hidden insight. Empathy changes everything: Recognizing procrastination as neurological dissolves shame, promoting self-advocacy and opening the door to solutions tailored to your unique mind.

- Evidence-based strategies target executive function: Interventions such as medication, cognitive-behavioral therapies, structured routines, and technology-based aids specifically address ADHD-related procrastination by working with the brain’s wiring.

Viewing ADHD procrastination as a matter of brain biology rather than personal failure transforms how you approach change. This understanding helps you replace self-blame with practical, supportive systems that help you flow, focus, and follow through. Let’s take a closer look at the science and practical strategies that empower you to finish what you start.

Introduction

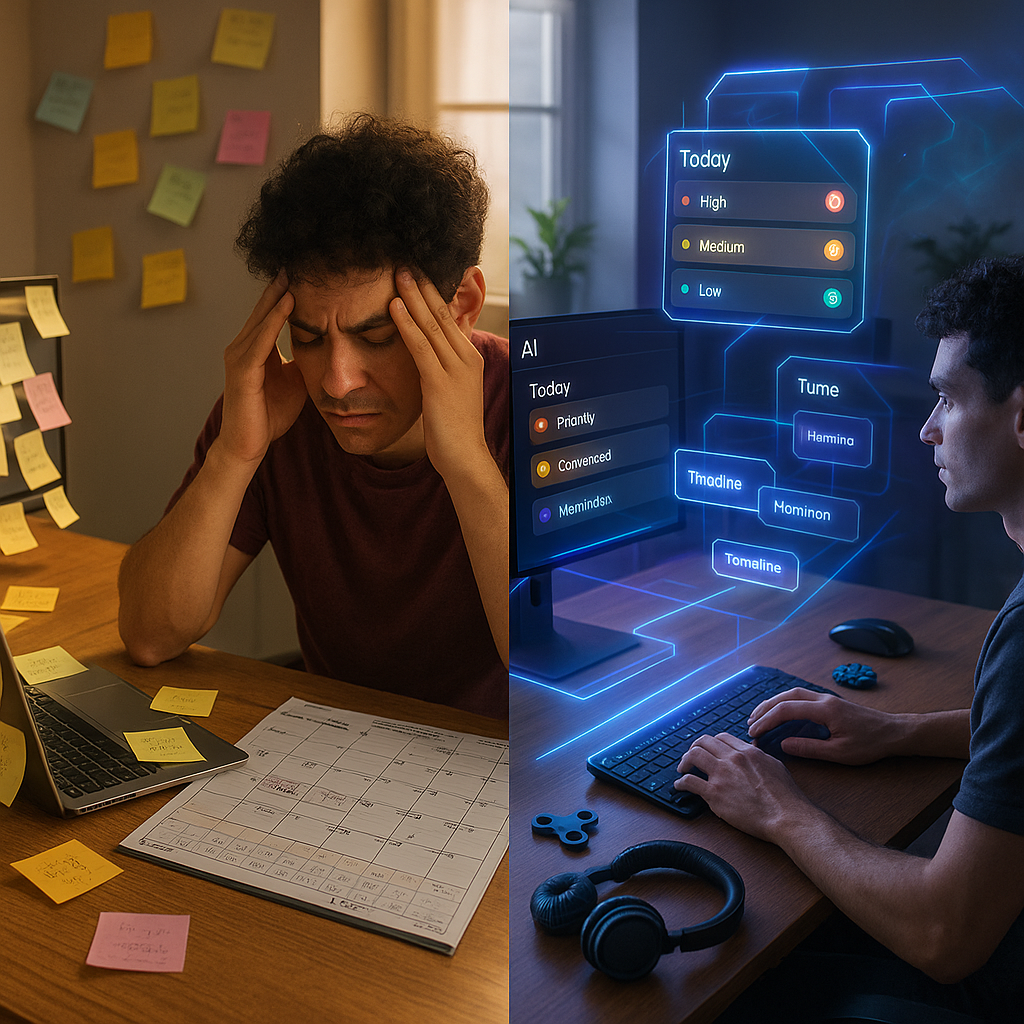

Have you ever wondered why your to-do list seems untouched, even when you genuinely want to make progress? For people with ADHD, procrastination isn’t about laziness or a lack of willpower. It arises from the way the ADHD brain handles motivation, focus, and time.

Identifying the real roots of ADHD procrastination changes everything. Understanding the neurological factors behind trouble with task initiation, the subtle sabotage of self-regulation and time blindness, and the shortcomings of traditional productivity systems lifts the weight of unnecessary shame. Effective solutions are built not on more grit, but on external systems crafted to support your unique way of thinking.

Discover how reframing procrastination as a neurological issue unlocks proven, ADHD-friendly strategies, and see how you can move from feeling stuck to taking purposeful action.

Procrastination is Not a Character Flaw: The Neuroscience of ADHD Delay

For people with ADHD, procrastination is not simply an issue of poor time management or lack of effort. What may appear to others as avoidance or laziness is actually rooted in fundamental differences in brain structure and function. These neurological realities create a version of procrastination that neurotypical people rarely experience or understand.

Scientific research, including brain imaging studies, reveals that individuals with ADHD have differences in areas of the brain responsible for executive functioning, particularly the prefrontal cortex, which governs planning, decision-making, and starting tasks. This is not a flaw in character, but a tangible difference in brain wiring.

Dr. Russell Barkley, a prominent ADHD researcher, clearly summarizes this distinction: “ADHD is not a problem of knowing what to do; it’s a problem of doing what you know.” People with ADHD typically understand what needs to be done. The challenge lies in reliably taking action, due to neurological barriers.

Recognizing the biological basis behind ADHD procrastination is transformative. No longer viewed as a moral failing, it becomes a symptom requiring understanding, accommodations, and strategies tailored to how ADHD brains function best.

The Executive Dysfunction Connection

What is Executive Dysfunction?

Executive dysfunction is central to ADHD-related procrastination. Executive functions are the brain’s management tools, responsible for planning, prioritization, working memory, task initiation, and emotional regulation. In ADHD, these processes develop differently due to changes in prefrontal cortex activity and dopamine regulation.

The most relevant executive function challenges associated with procrastination include:

- Task initiation difficulties: Struggling to start tasks, even when they’re necessary

- Time blindness: Trouble perceiving time and estimating task duration

- Working memory limitations: Difficulty keeping task steps or requirements in mind

- Prioritization hurdles: Problems determining which task to tackle first

- Emotional regulation issues: Trouble managing the negative feelings certain tasks provoke

These challenges are interconnected. Together, they create a perfect storm for procrastination. Importantly, these issues are neurological, not simply a matter of poor motivation or discipline.

How Executive Dysfunction Creates Procrastination Patterns

Executive dysfunction leads to multiple, familiar patterns of procrastination for those with ADHD:

- The activation hurdle: Starting feels like pushing through invisible resistance, making even simple tasks seem insurmountable.

- Interest-based motivation: ADHD brains are driven by what is interesting, novel, urgent, challenging, or emotionally engaging. Tasks lacking these elements are much harder to begin.

- Paralysis by analysis: Overwhelm and difficulty breaking down complex projects leads to total avoidance.

- The perfectionism trap: Anxiety about doing a task perfectly can delay starting, ironically increasing the chances of a rushed or less-than-ideal outcome.

- Out of sight, out of mind: Since working memory is limited, tasks and deadlines not visually or physically present can easily be forgotten.

These persistent struggles occur despite strong intentions and sincere effort. The underlying issue is not about trying hard enough, but about the interplay between neurological function and executive control.

Beyond Willpower: The Motivation-Action Gap

The Dopamine Deficit

At the biochemical level, ADHD procrastination is deeply connected to dopamine, a neurotransmitter that drives reward, motivation, and the ability to take action. ADHD brains often have fewer dopamine receptors in essential areas, lower baseline dopamine during routine tasks, and inefficient recycling of this chemical.

Dr. William Dodson describes the concept of an “interest-based nervous system.” While neurotypical people can complete tasks based on importance, those with ADHD rely on interest or urgency (a direct reflection of dopamine’s role). The challenge is not in willingness, but in the brain’s neurochemistry. Tasks that do not trigger sufficient dopamine rarely get started, no matter how significant.

This is why strategies that work for neurotypicals often fall flat; the neurological bridge from intention to action is missing unless dopamine is effectively activated.

The Wall of Awful: Emotional Barriers to Action

On top of neurological obstacles, people with ADHD face the added pressure of what some call “the wall of awful,” an emotional barrier that builds up over time. This wall is formed by:

- Shame and guilt over past procrastination episodes

- Anxiety about failing or making mistakes

- Overwhelm from breaking down large or complex tasks

- Rejection sensitivity and fear of criticism

Every instance of procrastination adds another emotional layer, making future task initiation even more daunting. The cycle is self-reinforcing: shame and anxiety deepen avoidance, which causes more shame and anxiety.

Psychologists describe this as “moral distress,” the persistent, painful feeling of failing to meet your own intentions even though your effort is sincere. Addressing this wall requires compassion, self-awareness, and practical support, not just increased willpower.

The Procrastination-Anxiety Cycle

How Anxiety Fuels Procrastination

Anxiety and procrastination often fuel each other, forming a vicious cycle. For people with ADHD, anxiety activates the brain’s threat response system, which undermines executive function by:

- Reducing activity in the prefrontal cortex (where planning and regulation occur)

- Triggering stress hormones that cloud judgment and working memory

- Promoting avoidance behaviors as a temporary means of relief

This means the very mental capabilities needed to overcome procrastination are weakened precisely when anxiety is at its peak. As one delays, anxiety grows, which further impairs executive function, creating a powerful feedback loop.

Dr. Thomas Brown’s research underscores how emotional experience is tightly woven into executive functions for people with ADHD. The practical takeaway is clear: advice to “just power through” fails because it ignores how anxiety disrupts the neurological foundation for action.

Breaking the Emotional Cycle

Effectively breaking the cycle of procrastination and anxiety requires addressing both the executive function and emotional sides:

- Self-compassion practice: Treat yourself with the same kindness as you’d offer a friend. Dr. Kristin Neff’s work shows this approach reduces procrastination more than self-criticism.

- Cognitive restructuring: Catch negative thought spirals and gently reframe them. For instance, challenge thinking like “I’ll never get this done” with “I can take the first small step.”

- Body-based regulation: Use breathing, short exercise, or grounding techniques to reset stress and bring the rational brain back online.

- Emotional validation: Acknowledge that avoidance is a response to authentic emotional barriers. This self-acceptance reduces shame and allows for problem-solving.

By integrating these approaches, you do more than treat symptoms. You begin resolving the emotional blockers at their source and restore the brain’s ability to move forward.

Strategies That Work With Your ADHD Brain

Interest-Based Task Design

Instead of battling your brain’s motivation wiring, design your work and environment to activate interest, novelty, and urgency:

- Introduce novelty: Shake up routines with new workspaces, colorful or unique supplies, or fresh approaches.

- Make it a challenge: Set time-based goals or friendly competitions to harness your drive for novelty and achievement.

- Create urgency: Set artificial deadlines, use timers, or involve accountability partners to make tasks feel time-sensitive.

- Use body doubling: Work alongside someone else (either virtually or in person) to anchor your attention and boost motivation.

- Connect to deeper meaning: Link boring or tedious tasks to your core values or bigger-picture goals.

These strategies are backed by evidence. For example, a 2018 Journal of Attention Disorders study found that when mundane tasks are gamified or framed as personal challenges, adults with ADHD perform as well as non-ADHD adults. The aim isn’t to make everything entertaining, but rather to introduce elements that naturally stimulate your brain and help you get started.

Applications of interest-based task design can be seen across industries. In education, gamified lessons and time-limited classroom challenges help students with ADHD stay engaged. In healthcare, structured team huddles or shift-change checklists can inject necessary urgency for staff with neurodivergent wiring. Even in finance and legal sectors, using “power hours,” visual dashboards, and collaborative work sprints can tap into this dopamine-driven motivation.

Environment Modification for Executive Function Support

Your surroundings have a direct impact on your ability to focus and follow through. Consider strategies such as:

- Visual cue systems: Use color-coded reminders, sticky notes, or digital dashboards to keep priority tasks visible.

- Minimalistic workspaces: Reduce distractions by decluttering and keeping your physical or digital workspace streamlined.

- Task staging: Place necessary materials and instructions out and ready the night before to lower the activation energy required to start.

- Accessible tools: Utilize ADHD-friendly apps and physical aids like whiteboards, timers, or progress trackers.

These environmental supports are just as effective in professional contexts. In marketing, digital campaign boards with vivid visual cues help teams keep track of deadlines and assets. In education, classroom visuals foster better homework management. Healthcare teams use color-coded patient charts to reduce missed steps. For retail managers, prominent signage and inventory checklists can transform workflow adherence.

Evidence-Based Tools and Interventions

Effectively managing ADHD procrastination requires evidence-backed solutions targeted at executive function. These include:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT): Helps break harmful thought patterns and build effective routines.

- Medication: ADHD-specific medicines can improve dopamine activity, strengthening executive functions and making task initiation smoother.

- Routine optimization: Break large tasks into actionable micro-steps, celebrate small wins, and use consistent cues (alarms, alerts, or written checklists).

- Technology aides: Apps for time tracking, digital accountability partners, or smart calendars that send nudges and reminders.

- Professional support: Coaching or consultation with ADHD-informed experts, whether in clinical practice or workplace productivity, to provide tailored, ongoing feedback and support.

Every industry can harness these supports. Legal professionals benefit from contract management software with built-in prompts. Environmental scientists use project management tools with milestones to keep fieldwork on track. Financial and healthcare organizations leverage automated reminders and workflow systems to keep neurodivergent team members on schedule.

Conclusion

Looking at ADHD procrastination through the lens of neuroscience replaces blame with clarity and opens the path to meaningful change. We now understand that procrastination for those with ADHD is not rooted in weakness, but in a complex interplay of executive dysfunction, dopamine regulation, and emotional barriers, each shaped by authentic neurological differences.

This shift in perspective reduces stigma and empowers individuals to seek compassionate, tailored strategies: external systems, self-kindness, and supportive routines designed for how their unique brains work best. At ADHDink, we see thriving with ADHD not as a matter of fitting into neurotypical frameworks, but as the power to design systems that harness your creative, nonlinear strengths.

As the world becomes more complex and fast-paced, organizations and individuals who adapt their environments, tools, and habits to embrace neurodiversity will lead the way in unlocking human potential. The future belongs to those who transform challenges into tools, and who outsmart procrastination with systems as dynamic as their minds. The real opportunity isn’t simply to beat procrastination, but to leverage it as a catalyst for smarter, more authentic productivity. What tailored system will you build to spark your next breakthrough?

Leave a Reply